hello from (southern) corea!

ji-youn in corea #1

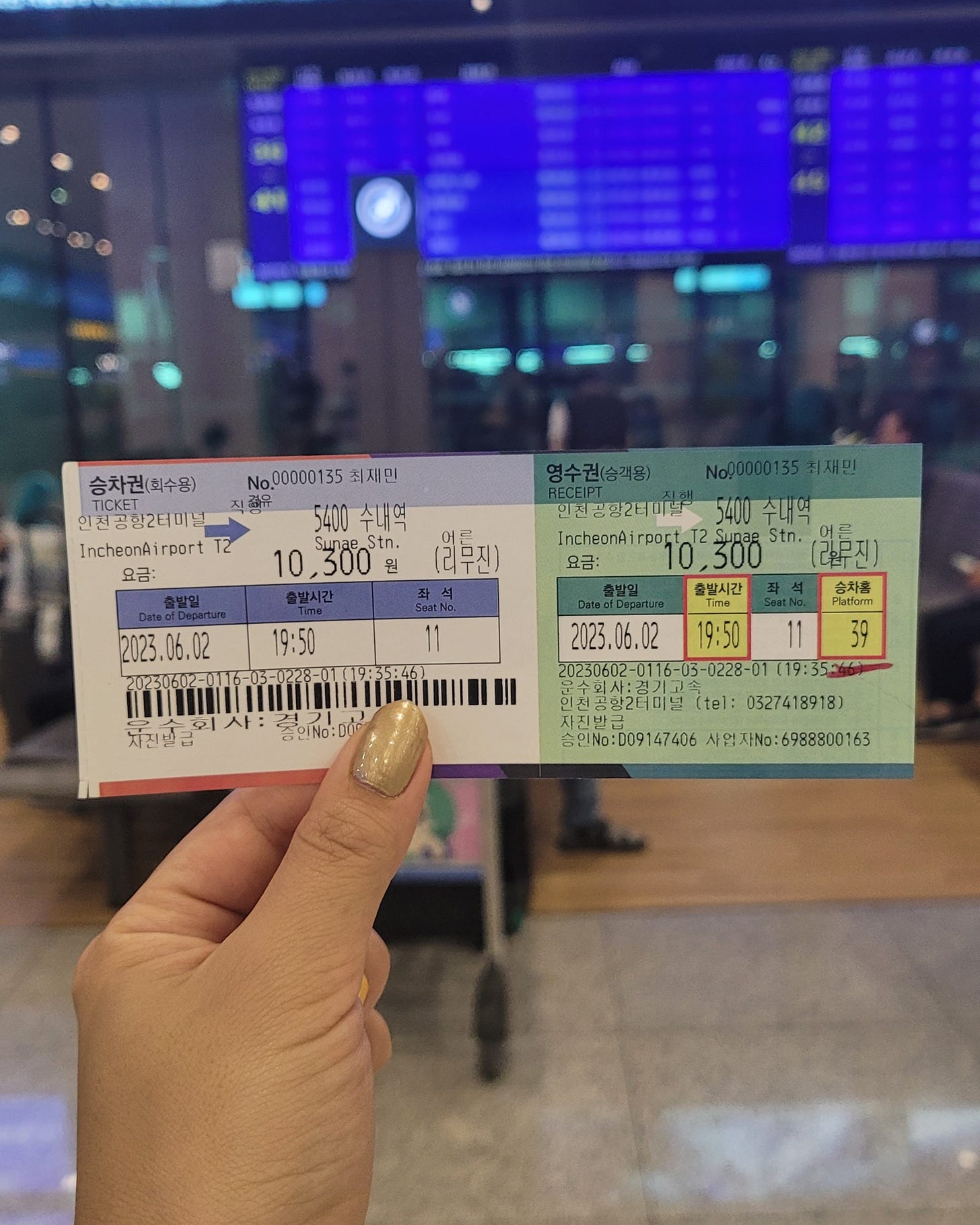

it has been 5 days since I arrived. I've been thinking about writing a first post for the past two weeks — both leading up to the trip and in the first few days of arriving. but I think I've been delaying it because I'm only now finally starting to accept the reality that it’s here. I'm doing it.

for the two weeks leading up to my flight, friends asked how I was feeling about it, feeling excited for me. while I received their excitement with joy, I shared that I felt a background buzzing of mixed emotions: panic, excitement, anticipation, worry, disbelief, and grief of all sorts. when I visited corea for 2 weeks last december, I experienced both deep grief and immense joy. I'm expecting a similar-ish experience for this long visit, but extended, maybe less intense and more of a quieter murmur. this 5-month visit is different in many other ways. to name a couple: for the most part, this is a solo trip without the guidance of my parents and/or sister for language or their support in emotional processing. I'm also visiting other parts of the country beyond seoul and the nearby cities, in hopes of learning more about the specific histories of the land and peoples.

visiting the "homeland/motherland" is nothing like going on a vacation to another country (though vacationing is not empty of critique/processing either, as tourism is often implicated in imperialism, and it's important to me to be conscious of my relationship to power wherever I travel).

as an asian settler who grew up and resides on turtle island in so-called canada, my relationship with "home" and "homeyness" is in constant flux. Nandita Sharma talks about who gets to claim "homeyness" in so-called canada, shaped by race and categories ranging from "citizen" to "illegal" and how racialized migrants must be perceived as a potential threat to strengthen white settler nation-building.1 I also think about Sara Ahmed's description of the dominant construction and understanding (ie. white settler colonial construction in the west) of home as "as a purified space of belonging in which the subject is too comfortable to question the limits or borders of [their] experience, indeed, where the subject is so at ease that [they] do not think" (339).2 this is a construction of home that is not granted to migrants (and is rather exclusive to white settlers on turtle island). home becomes partial. and this fragmented sense of home for migrants is in significant contrast to expats or those who choose "the nomadic life", as many migrants often leave their home countries due to a degree of forced displacement. sarah ahmed also talks about "Home through the very failure of memory... The very failure of individual memory is compensated for by collective memory, and the writing of the history of a nation, in which the subject can allow herself to fit in by being assigned a place in a forgotten past" (330).3 I'm still very much sitting with this last piece. my family immigrated when I was 5 years old. I grew up in proximity to corean language and learning a lot about corean history from my parents — collective memory. I feel like I have a felt sense memory of the colourful and bold signage of shops, the varying types of candy and snacks, and of course, the language. but there are many, so many gaps — the failure of individual memory. there is both a sense of familiarity and unfamiliarity at the same time in being here.

in the practice of thinking about sovereignty, I also think about my relationship to colonial white supremacy. while I am not a settler on these lands, while I do have an ancestral relationship to these lands despite not (yet) having much of a physical one, I'm aware that I can so easily bring in western imperial ideology. it's so fucked up, how I feel a sense of superiority (power that is given to me by mainstream society) due to my perfect english accent (and of course, being bilingual with a near-perfect corean accent). I'm constantly mindful of how I may be subconsciously inserting western imperial ideology into how I experience corea. I also experience tremendous grief in how american imperialism and capitalism have such a strong grasp on mainstream society here.

given all of these layers, one of the main questions I am exploring during this long visit is: what is the anti-imperialist role of corean diaspora, in both corean sovereignty and indigenous sovereignty on turtle island and around the world? I am familiar with thinking about the second part of the role of asian settlers on turtle island, but am much less familiar with what my role is in regard to corean sovereignty. corea continues to be divided through american militarism, and there are present-day efforts to erase imperial japanese history. at the same time, it's important to remember that there are coreans in the rok who are in resistance, who are continuing the legacy of our freedom fighting ancestors, and folks of corean diaspora have a role to play. I'm looking forward to the exploration of this role and how it will shape my sense of homeyness here in corea.

here's a first braindump sharing a fraction of my thoughts/processing of being here in southern corea. I imagine I'll share similar snippets of my processing, as well as some things I learn (like words or history) and experience (food? grief? joy?) in the weeks and months to come.

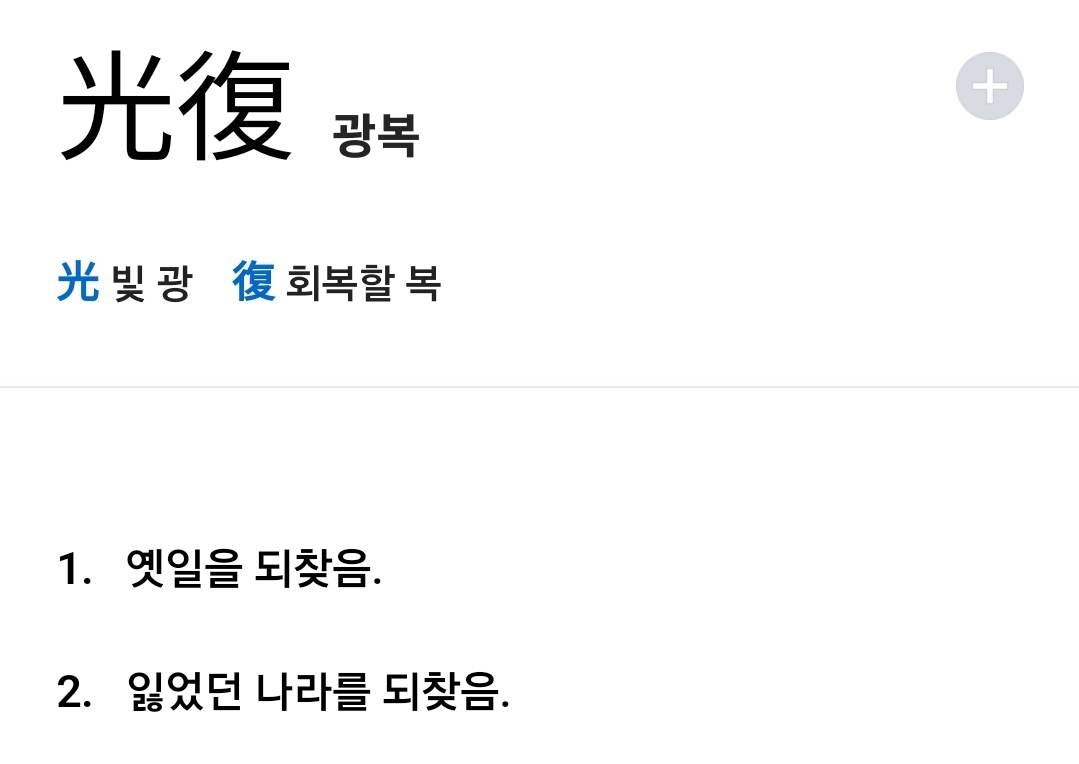

to close for today, I want to share a corean word I recently learned that is related to the topics above.

광복 (pronounced gwang-bok) means independence, to regain, or to regain independence as a country. the hanja is composed of 광 (光) meaning "light" and 복 (復) meaning "return".4

I came across this word on the subway a few days ago, where they display ads and poetry and other info/campaigns. june 25th (6.25) marks the first day of the korean war in 1950 and so there was a historical info campaign on the subway to honour some freedom fighters. I won't go too into this now, but I want to remind folks that while the korean war is often discussed as a war between north and south korea, corea was a battleground for the US and soviet union in their cold war. English discourse will describe the US as (southern) corea's saviour from japanese imperialism, but it's important to remember that the US and USSR separated our country. many of our freedom fighting ancestors (including 김구 선생님 Kim Gu) were strongly against this separation and wished for a unified, truly soverign corea.5

ok, that's plenty for today. hello and welcome to the fellow diasporic koreans/coreans reading about my journey as you are my main intended audience! and hello and welcome to everyone else (but just know I'm in the practice of rejecting the white gaze as I write/process).

Nandita Sharma, “Nation States, Borders, Citizenship, and the Making of National Difference,” in Power and Everyday Practices, ed. Deborah R. Brock, Mark P. Thomas, Rebecca Raby (Toronto: Nelson Education, 2012).

Sara Ahmed, “Home and Away: Narratives of Migration and Estrangement,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 2, 3(1999): 339.

Sara Ahmed, “Home and Away: Narratives of Migration and Estrangement,” 330.

many corean words are derived from hanja, chinese characters, and thus have deeper meanings to them! corean sounds don’t stick for me, so I learn new corean words through learning the hanja. this helps me learn a bunch of other words with the same characters.

I’ll be writing about 김구 선생님 later down the line! visiting his memorial hall in december was such a big part of my trip last time and I plan on visiting again soon.